Lead vocalist Wency Cornejo asked this question around thirty years ago when the song "Next in Line" ruled the local radio airwaves. And now this question is top of mind because for the past month, the source of public uproar is the Maharlika Wealth Fund, which this Department of Budget and Management PR describes as "a sovereign wealth fund which will be used by the government to invest" in, among other things, "foreign currencies, fixed-income instruments, domestic and foreign corporate bonds, commercial real estate, and infrastructure projects."

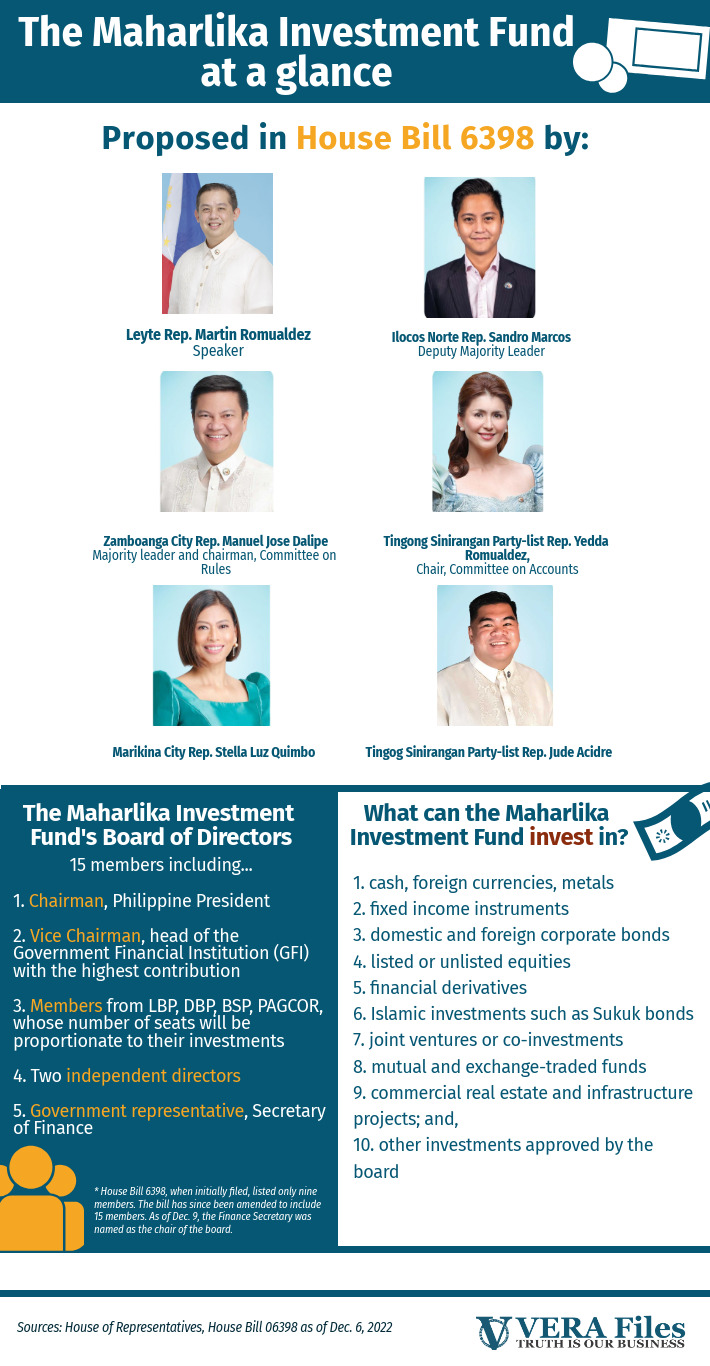

First off, the name itself is sus (as young folks say). "Maharlika" is technically the feudal warrior class, but the ordinary Pinoy understands it as the nobility class -- or the alta and elite in our society. What's more shady though is its association with the elder Marcos: it's the title of the 1970 film which stars his mistress Dovie Beams and detailed the supposed (and fictional) exploits of Soldier Marcos' bravery during World War II -- a sham that's been proven several times over, but has been dusted and peddled anew to rebrand the Marcos years as the country's "Golden Age." (Interestingly, "Maharlika" has apparently been re-released in 1987, after the dictator has been ousted. The poster above is from the Video48 blog.) Who's behind this scheme? Now we get the younger Marcos' cousin Ferdinand Romualdez, his wife Yedda and another same party list cohort, Bongbong's son Sandro, a representative from Zamboanga who is probably is also a close "family" associate, and a surprise stooge in "Teacher" Stella Quimbo of Marikina---sooooo disappointing, btw--pushing the HB6398 proposal in Congress and that they want to certify as "urgent."

Then there are the government shills. In the DBM's PR piece, current Secretary Mangandaman, shares her "optimism" on "behalf of the Economic Team." Joey Salceda and Finance Secretary (and former BSP Governor) Benjamin Diokno want us to believe that this fund that wants to "invest" the GSIS and SSS pension funds of our citizens in a scheme that doesn't have enough checks and balances that could leave destitute our future senior citizens, hardworking ordinary folks who are counting on these pensions in their old age.

How the fund proposes to earn is by putting our hard earned money in derivatives (a complicated financial instrument that played a role in the 2008 financial crisis), "alternative investments" like unlisted equities, which are "shares from a company that are not registered in the stock market."

Later on, the proponents even said that they would use MWF to "take back control" of our National Grid because it was being run or controlled by the Chinese -- which are actually the Sy (of SM) and Coyiuto families.

There are already many articles online that explain in more detail why the Maharlika Wealth Fund is dangerous. Vera Files has an amazing fact sheet.

Ricardo Saludo of the Manila Times asks, "What's in it for the poor?" Something that was "hardly asked in the debates," he noted, as it mostly focused on investment risks and transparency issues. Saludo asserts that the MWF is not a "strategic" thing to do for a "less endowed country" such as ours. Sovereign wealth funds are usually "what prosperous, progressive nations do." Is the MWF the right thing to do when your country is battling inflation, doesn't have sustainable pensions for its senior citizens, and insists that P488 is enough for a bare minimum nochebuena of 5 people?

There are many things the Philippines should be considering before establishing a sovereign wealth fund.

Heck, even the immortal Enrile remarked that we should "carefully review" the MWF.

One of the more shocking (or maybe shouldn't be shocking) pieces of information I found out in the course of following the Maharlika debacle is that only 20% of senior citizens (defined as age 60 and over) in the Philippines benefit from a retirement fund system. This presentation by Christian Mina and Faith Cacnio, which I found through the PSA website, asks if Filipino senior citizens are financially protected, and they presented evidence based on a consumer finance survey. Their survey and data set is from 2014, but I think it's still relevant for the purposes of this post.

Mina and Cacnio found out that social security in the Philippines was linked with the "formal employment," so basically people with regular jobs.

Mina and Cacnio's main takeaway from this survey is that the vast majority senior Filipino citizens (or around 75%) who were their family's breadwinners (or "economically dominant persons" according to the document's preferred jargon) were not covered by retirement plans.

Of the 20% who receive pensions, the split was 15-16% from SSS (or the private sector) and 4% from GSIS, or those with government jobs. But they also characterize SSS pensioners as belonging to the "poorest 40%" and were likely to be receiving monthly payouts of P4,000 or below. Meanwhile, only 4% (we're assuming these are the GSIS pensioners) are getting Php 30,000 or more, an amount that's more likely to cover their consumer expenses.

There's a real divide between the economic situations of SSS and GSIS members in retirement, with those who worked in government jobs more likely to own a house with 3-4 bedrooms and built with sturdy materials, own a business, smaller number of dependents -- most of whom are old. The SSS pensioners are more urban, poorer, have smaller houses built with less durable materials, and are likely to be supporting younger dependents.

It's also worth noting that those 60 years old and older in 2014 were born 1954 and earlier -- so definitely Boomers. They worked hard and are getting something but still not enough.

And we're not even considering those who are NOT covered by either the SSS or GSIS. Mina and Cacnio characterized them as having had little education ("some elementary"), no real properties, and their homes have "0-1 bedrooms" made of light materials, have no deposit accounts, no emergency money at home, supporting more dependents, and most likely male. These are the manongs who worked "casual" or contractual jobs, but most likely they belonged to the "gray" or informal economy, who made the most diskarte. The DSWD does support indigent senior citizens, but that's a measly Php 500 a month. But guess what, even that is not enough when you go down the line.

And what about us who are currently part of the labor or workforce? Can we still depend on the GSIS or the SSS in, say, 2040?

Boo Chanco's Philstar column from December 12 ("Pension funds") stated that last October, the Philippines was declared to be the "second worst among 44 economies in Mercer-CFA Institute’s Global Pension Index." The main reason: retirees not getting sufficient pensions. Mercer's Global Pension Index evaluates funds according to three criteria: adequacy, sustainability, and integrity. The Philippines ranked last of 44 countries in the integrity criteria, which looks at how a retirement system is regulated, how members are protected, and how much it costs to operate the fund. In terms of sustainability, remember when the late PNoy vetoed adding Php1,000 to pensions, citing the danger that it would cut the fund's life shorter by 7-12 years? Then Duterte shrugged and said, "Give it." That meant the fund can only last until 2047.

If life permits, I would be among those retiring (or retired earlier, yeah?) in 2048. But by then, THERE. WOULD. BE. NO. MORE. FUNDS.

So paano tayong mga nagbabayad ngayon? Nganga na lang? Will you still want to contribute to your SSS (and even Philhealth!) if you know you will most likely end up broke even if nag-ipon ka naman? Yes, I understand that the point of these funds is that the current working population is supporting those who worked before and are retired now, and the future generation will support us. Pero paano nga kung di na sapat ang funds? Or if the House of Representatives, the Senate and the current admin's stooges all have their way and use the Maharlika money (our money!) to somehow fund their misguided vendetta against "the Chinese" running our National Grid? Or if they invest in the companies of cronies? Do we get a say then?

What's remarkable is that the millions of SSS and GSIS current and future pensioners voiced out their anger and that allowed for a few backtracking bits. But if the Speaker of the House wants this bill certified as "urgent" so his cousin can sign it, what now? What then?

It's no wonder that retirement and familial support is froth with tender wounds and difficult decisions.

In online discussion boards and even social media, the current generation of workers and breadwinners is starting to push back against the widespread belief and practice that the "anak as retirement fund." It's so bad that there are "Panganay Support Groups," with a very specific "eldest daughter in an Asian household" slant. The ongoing narrative is that of greedy and abusive parents basically gaslighting their children into "giving back" more and more support, of asking the elder child to finance the education of younger siblings, of funding the family expenses, that it is the child's responsibility to lift the family out of poverty ("iahon sa kahirapan"). (If you want tea of this kind, just search for online gamer H2WO's problem with his mom. It's a long read, but typical of the parent asking excessive financial support from their kid narrative.)

But really, when you really look at it, it's not entirely the fault of the previous generation. Filipinos are "indisposed" to saving -- maybe because we don't even have enough for the day to day to begin with. How can you think of the future if today's hunger has to be fed?

This is where the government steps in. The State should take care of its people. Not just its own. But everyone. But if certain people get their way, all that is ours is theirs.

No comments:

Post a Comment